NEW! James Webb Space Telescope success story: try, test and win!

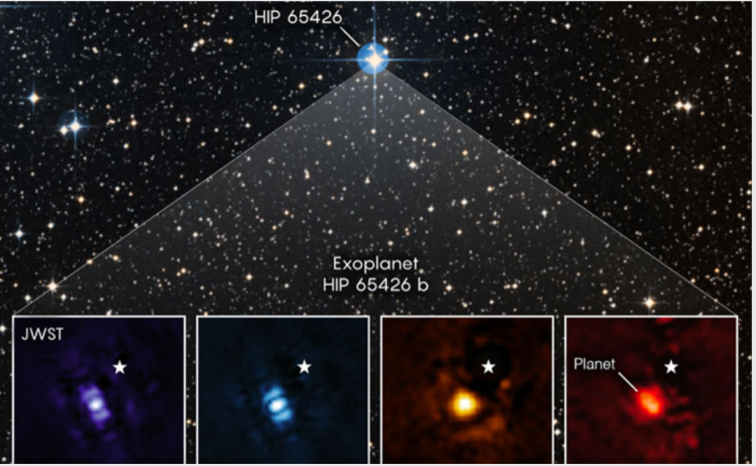

Extrasolar planets are detected in several ways, of which the most convincing, but also the most difficult, is direct imaging. And that’s exactly what the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) managed to do recently: it recorded its first extrasolar planet and that directly!

So, not indirectly, when it is actually about observing the consequences caused by the planet (say, in regular periods it blocks part of the light of the parent star), but the Webb telescope recorded the planet directly. Of course, it’s a bright spot, not a photo showing the planet’s surface.

But this spot also provides astronomers with a series of valuable data, so they calculated and determined the following: the spot, which is otherwise called HIP 65426 b, is seven times more massive than our Jupiter; it orbits the star HIP 65426 (the letter b is the planet’s designation), which is 400 light-years away from us.

This image is very encouraging because it is ten times better than expected, which means that JWST is able to image smaller planets than the one it captured.

When directly imaging an exoplanet, the problem is the shadowing light coming from the parent star. That’s why JWST used a tried-and-tested trick, and with the help of a small mask, which is actually a coronagraph, it blocked the star’s light and thus managed to spot the planet, which normally has a thousand or more times weaker brightness than the parent star.

JWST meets Earendel the star

Since the Hubble Space Telescope recorded the oldest and farthest known star Earendel at the beginning of the year, we have been waiting impatiently for the new James Webb Space Telescope to record the same star.

And guess what? This is precisely what happened this summer! And scientists immediately threw themselves into analysis and interpretation, and here is what they concluded.

The material from which the first stars were made, namely hydrogen and helium, were formed about 380,000 years after the Big Bang, and the first galaxies were formed about 400 million years later. So where does this lead us?

Well, this means that the first stars were formed somewhere between those two events. It is not known for sure exactly when, but according to some estimates it was about 100 million years after the birth of the cosmos.

This was only a theoretical estimate without direct observational confirmation, and the oldest observed star until this year was formed a full 4.4 billion years after the Big Bang.

It must be said that there was a lot of luck involved with the Earendel star. In fact, almost incredibly too much luck because its position coincided behind a huge cluster of galaxies (VHL0137-08) whose gravitational field focused the Earendel star like a gigantic lens, magnifying it as much as 40,000 times!

The star ignited 13 billion years ago, but due to the expansion of the universe, it is now 28 billion light years away from Earth.

The surface temperature of Earendel is between 13,000 and 16,000 degrees (on any scale), and based on the temperature, astronomers conclude that it is a giant B-type star that burns hydrogen and has a mass somewhere between 20 and 200 times the mass of the Sun.

It is possible that it is actually a binary star, a cold star with a hot companion, and that is a good assumption, but without clear confirmation.

In order to learn more about this star, more observations are needed, and one such being when JWST takes another look at it later this year.