The unusual life of a 18th century female astronomer: Caroline Herschel

Until the previous century, the history of astronomy was dominated by great discoveries made by great scientists, such as Tycho Brahe, Galileo, Kepler, William Herschel and others. The number of women scientists who were recognized as innovators was very small.

A number of factors contributed to this, from social pressure to deprivation of opportunities in institutions and the lack of systematic scientific education. And yet, history records the occasional appearance of brilliant female scientists-astronomers; one of them is Caroline Herschel.

Uranus and the Herschel family

When the English amateur astronomer William Herschel discovered a new celestial body in 1781, at first it was not known whether it was a comet or a planet.

However, it was soon established that it was indeed a planet. It was named Uranus.

Its inventor became world famous and famous overnight. King George III himself received him, and soon granted him a salary for life, with the only obligation that he should settle near Windsor and be at the disposal of the royal family whenever he wished to look at the sky.

This offer could not be refused, and William moved together with his sister Caroline from Bath, where both he and Caroline were at the peak of their musical careers. For Caroline, it meant a turning point, leaving music and great uncertainty.

Childhood and youth

Caroline was born in 1750 in Hanover as the fifth of Isaac Herschel’s six children. It was undoubtedly a musically gifted family; the father and all four sons were talented musicians. The two sisters, Sofia and Karolina, however, were denied any education, except for the most necessary for household chores.

This was especially difficult for Caroline, who was eager for knowledge, and on the other hand, she knew that she would not be able to marry. Namely, childhood illnesses left indelible consequences on her; traces of smallpox were visible on the face, and after a bout of typhus, she was left with a short stature.

Her father wanted to teach her to play the violin, but her mother strongly opposed it.

During the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), which was being fought around Hanover, her beloved father died when Caroline was 17. William escaped the war by going to England. At the end of 1766, he got a position as an organist and after learning about the sad situation of his sister Caroline, he invited her to come to him in England.

From music to astronomy

In the 1777 season, Carolina sang several times as the first soloist. In the meantime, William found a new passion: it was astronomy.

Self-taught, he started building the biggest and best reflector telescope in the world only by reading books. His astronomical plans included a bigger role for Caroline, so he began giving her lessons in geometry, trigonometry and algebra. Caroline had to help him in every way, including copying the catalogs he used and the articles he sent to the London Royal Society.

Finally, in November 1781, William received the Royal Society’s Copley Medal for the aforementioned discovery of a new planet. The following year they performed together for the last time as musicians.

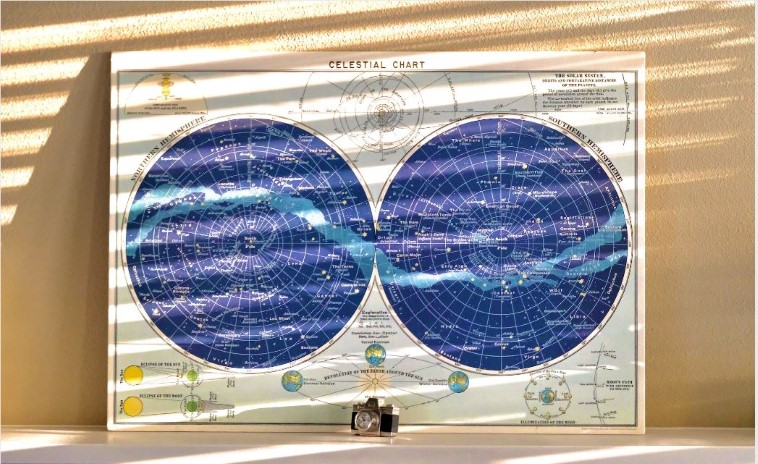

Wallpaper by sherbakmak on Wallpapers.com

However, William had big plans for her. He gave her a special telescope with which she was supposed to search the sky, looking primarily for comets, but also for other celestial bodies such as binary stars, nebulae, star clusters.

It took several months for Caroline to settle into the role of assistant astronomer and begin to enjoy the searches. The turning point came in February 1783, when she first found two nebulae that were not in the existing catalog of the French astronomer Messier.

In the following months, she found two more, as well as one star cluster. Less than a year since her last performance as a soprano, Karolina had increased the number of famous nebulas in astronomy by 5%!

New horizons through teamwork

Her successes opened William’s eyes. He decided to devote himself to the search for nebulae, with his new “large” 6-meter telescope.

They managed a lot through teamwork: William would watch, waiting for the rotation of the sky to bring the nebula into his field of vision, and Caroline, sitting nearby, would write down what he would say to her, and then repeat out loud what she wrote down.

Every morning Caroline would copy her nightly notes, make the necessary calculations and prepare for the catalog. When the brother and sister began their search, astronomers only knew about a hundred nebulae from Messier’s catalog; by the time they finished, that number had grown to 2,500.

This huge project lasted about twenty years, until around 1802.

In 1782 while William was away, she noticed an object which later turned out to be a comet. It was her first comet, Hershel (C/1786 P1) and also the first comet discovered by a woman, the first “lady’s” comet.

More findings as solo astronomer

After the marriage of Caroline’s brother to a rich widow in 1788, she was able to dedicate herself more to independent work. Still the same in 1788 – she finds another comet, which is now called Herschel-Rigole (P35).

Carolina discovered two comets in 1790, Herschel (C/1790 A1) and Herschel (C/1790 H1), and in 1791, Comet Herschel (C/1791 X1). Her last discovery was Comet Bouvard-Herschel (C/1797 P1), which was also observed by the Frenchman Eugène Bouvard, so the comet bears both names.

In June 1799, she began to recalculate the positions of the stars that were used as starting points in the great search for nebulae. Due to the precession of the Earth, the North Celestial Pole is constantly moving and the positions of the stars relative to the Pole must be given for each particular epoch.

In February 1828, the Royal Astronomical Society awarded Caroline Herschel the Gold Medal for this work of immense importance to astronomy. No woman received this distinction until Vera Rubin, in 1996.

She died in 1848, at the age of 98. Her original contributions, especially in the discovery of comets and in a new, user-friendly approach to cataloging celestial bodies, make her one of the greatest astronomers of all times.